Tastes Good with Tag Christof

Ten food questions with an editorial and documentary photographer

Looking at Tag Christof’s photography changes the way you see the world. You can’t help but notice the tiny details of a flower blooming in an abandoned parking lot, or the exquisite beauty of a mundane object. His work transports you. Whether it’s the story of a forgotten shopping mall slated for demolition, that captures the architectural detail of a bygone era, or the soft fluid lines of a classic car, Tag uses his camera to create a radical new vision of the world.

With a background in architecture and industrial design, Tag learned photography on the ground in Milan, Florence, New York City, and London. He recently told me about a series of photos he’s been taking of diner food, and I knew I wanted to interview him for Tastes Good. Tag spends nearly half his time on the road, eating in greasy spoons and staying in mom-and-pop motels, because, as he puts it, these are “the likeliest places to meet the unlikeliest people.”

You can read our Q&A below.

You grew up in Northern New Mexico. What was food like in your family?

I had no idea how special the places I grew up were. We fished for trout and crappie, hunted elk and deer, and were surrounded by orchards. I read books and played my Game Boy perched high in the branches of fruit trees. We took for granted the copious amounts of apples that fell to the ground and rotted at the end of every season. We ate the vegetables my grandparents grew, directly from the ground—peas, cucumbers, tomatoes, corn, garlic, chile, carrots, Jerusalem artichokes, arugula, ramps, melon—and foraged for verdolagas around ditches, for chanterelles and boletus mushrooms and tiny strawberries in the woods. We gathered piñon for roasting from under dry, scraggly trees. We ate green apricots with salt, way before they were ripe, when they're crisp and tart and explosive—there is no treat on earth better than a green apricot with salt. Rhubarb pulled straight from the plant (also with salt!), green apples, pears, plums, peaches, cherries and the blackest, juiciest grapes I've ever tasted. All I really want out of life is a sturdy little house surrounded by apricot trees and plenty of good salt. At home, we mostly ate standard New Mexican fare: lots of beans and chile, always home cooked. It was only after I'd gone away to college that I realized how precious few Americans, even the wealthiest ones, had anywhere near the close-to-earth, expansive experience with food I'd had as a child. I wish I had been more grateful for it at the time.

Much of your photography deals with the visual aesthetic of a long lost era. What nostalgic memories do you have of Santa Fe food life that don’t exist anymore?

Santa Fe has always been such a great crossroads of food culture. Years before Whole Foods came to town, we had access to an abundance of health food stores like Alfalfa's and Wild Oats that sold beautiful seeds and grains in bulk, lip-smackingly sour kefir totally unlike the mass-market candy in every dairy aisle today, and the occasional exotic fruit. We ate Chinese at least once a week at the late, great On Lok Yuen on Cerrillos, loved the Cioppino from old Pranzo, and ate elegant 90s sushi at the old white tablecloth Shohko Cafe when it was still a yuppie status symbol. I'd steal sips of plum wine from my mom's glass and always ask for mountains of that pickled, bright-pink ginger. The farmer's market, the way it used to be, was unselfconscious and shabby in the Borders bookstore parking lot, and a wonderful place to spend summer Saturday mornings. I remember strange greens and sprouts I'd never tasted before, Sweetwood Farms' pretty little wheels of herby goat cheese wrapped in neat red ribbons, bags of bee pollen from a lady whose hair looked like a family of birds lived in it, and cold pressed Velarde apple cider on sno cones.

When has food made you feel like an outsider? When has it made you feel like an insider?

I can only think of one genuine experience of going from feeling like an outsider to an insider: I lived in Italy for several years, primarily in Milan, and mostly because I dated a Fiorentino, I got the gift of partaking in countless little food-related habits and traditions one can never experience as a tourist. Things like quando si butta la pasta (the very serious matter of when precisely to drop pasta in salted boiling water); participating in the raccolta di olive (olive harvest) before hauling your ripe loot to the local frantoio to have it pressed into the most wonderful, fresh green-gold oil imaginable; sacrosanct little holiday traditions like tortellini in brodo for New Year's Eve; and how it's an offensive sacrilege to lazily nurse a cup of coffee beyond when it's hot and fresh. There's also the constant, good-natured discussions about the quality of ingredients, about technique, about seasonal changes—Italians by and large just don't sit down for a meal without considering their food, its source, and the ways it’s prepared. There really is something to learning, to internalizing, the humble, sometimes invisible little traits and traditions of a culture through osmosis.

You have traveled a lot, and even lived abroad for periods of time. What is a foreign eating experience that made you see food in a different light?

I once visited a friend and her dad in Poland. Her dad was this larger-than-life, rags-to-riches adventurer type, who'd moved to Chicago in the 1970s as an auto mechanic and returned to Poland during its post-Soviet liberalization as an automotive baron. He owned all the Nissan dealerships in Poland or something like that, and drove a crazy souped-up rally car around the cobbled streets of Warsaw at full speed. This man was thrilled to have an American guy visiting, and every dinner started with some variation of "You vill not leave zis table until zat is ALL gone! And zen we get more!," just as the waiter would put down some giant cut of meat in front of me. On that trip, I learned to enjoy tripe—a daunting, polarizing ingredient that can be genuinely ghastly in some preparations—and, for the first time in my life, learned both the purpose of and how to actually enjoy vodka. Good Polish vodka, sipped strategically, can really make the meal!

I have never in my life eaten as well as on that wonderful trip to Poland, and cannot believe that the world generally only thinks of Polish food as supermarket kielbasa, bland soups of flaccid cabbage, or the occasional pierogi. The wild mushrooms and perfectly-prepared root vegetables! The beautiful cuts of meat and fowl! The pickles! The sensational but subtle broths! And yes, the vodka! Polish cuisine is wonderful, and I'm just sorry I didn't learn about it earlier. I felt privileged to get this tour from an old man who so wanted to communicate his enthusiastic welcome to his country through it’s food.

What are the best and worst date foods? What is the sexiest food?

Oysters are obviously the sexiest food. They're probably not actually an aphrodisiac, but the act of slurping their soft bodies out of their gorgeous, iridescent shells, imagining the evocative locales they come from—the Mighty Rappahannock! Prince Edward Island! Desolation Sound!—and the intimacy of sharing them with everyone at your table is undeniably sensual.

I have only one weird food hangup, and it's been something I have tried but have been totally unable to overcome since childhood. You'll probably hate me for this, but I just loathe the taste, smell and texture of eggs, any style. Believe me, I wish I didn't: being unable to eat such an inexpensive, rich source of protein that chefs have done incredible things with since time immemorial makes eating around the world much harder than it should be. I used to lie and say I was allergic to them, but that's definitely not true, and I'd have to tie myself in knots to explain why I could gleefully eat baked goods full of a thing I was supposedly allergic to. Oddly, I can handle things like French toast, egg drop soup or even carbonara, because the egginess of those dishes are drowned out or made more complex and palatable by other flavors. I would rather lick the bottom of a boot than eat an omelet.

I was once on a date in Paris at a posh restaurant where the dishes all had artsy, abstract names—no descriptive or food words whatsoever. In an attempt to seem cool and chic, I pretended I wasn't flummoxed and just panic-ordered something that sounded inoffensive. It turned out to be a frittata, and I was horrified. I spent the entire meal trying valiantly not to gag or barf while choking down this awful, fat slice of egg pie, while also attempting to look beguiling. Of course, I failed spectacularly. It was our only date. Moral of the story: even in the snobbiest of contexts, it's better to just ask your server what you're ordering if you don't know. Especially if some common ingredient makes you want to hurl.

6. What do you eat before you go out on a shoot? Do you have any food rituals around making art?

I tend to do things a little last-minute, so in my pre-shoot rush, I usually just end up chugging an iced americano, black, with extra ice. I also invariably will regret not eating a proper meal beforehand, but clearly haven't learned my lesson yet.

What do you like about photographing food? How does it relate to your other photographic passions, such as architecture, cars, or portraits?

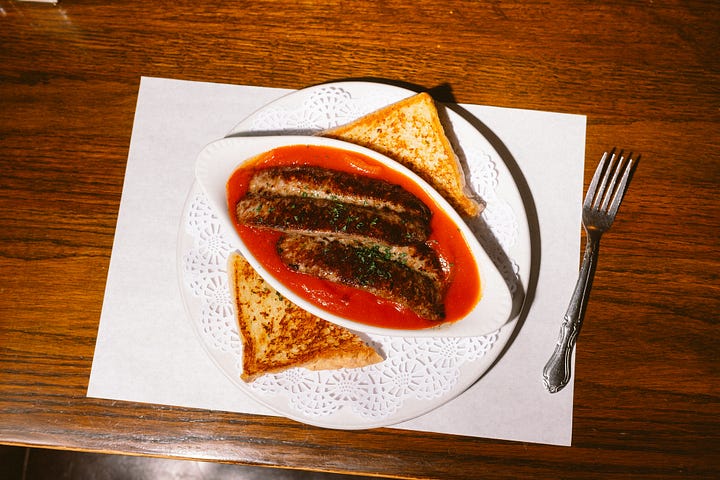

I don't photograph food in any traditional sense. These diner food photos are really the only explicitly food-centric part of my work. I've always loved Stephen Shore's style, especially the very textural 35mm work from his 1972 collection American Surfaces. It's a buffet of garish colors and mass-produced surfaces, all rendered in a particularly American color palette: vermilion reds, warm yellows, oversaturated greens. The magic mostly lies in the fact that when you look at this work in today’s time, it is instantly clear that the America he photographed looks very little like the America we now live in. I've been criss-crossing the country with a camera for many years now, and it strikes me that the only view that still looks more or less like Shore's America is what you see while sitting in a vinyl booth, looking down on a dish of diner slop. You are served a technicolor plate of symbols, one half-step above a TV dinner, often garnished with plastic parsley and an orange slice, out of habit more than anything. These dishes look like 1975, and in 2025, I love them. It's a minor form of time travel for me, rather than some bleary-eyed nostalgia.

An era is summed up by the texture of its spaces and objects. Ours feels overwhelmingly banal: smooth, dirty, blinding, indifferent. Every space is drowned in too-bright LED lighting, black-box screens mediate too many of our interactions, new architecture has been reduced to either incoherent blobs or indifferent modular blocks beholden to cost above all, interiors feel barren and practically digital, art is valuable only insofar as it's able to be represented on a social media grid. Food is self-consciously styled, gussied up not to be appetizing, but for maximum impact on the 'gram. A big part of my work is a search for those textural remnants of a more human time in America. It is a visual, metaphysical search for something like Robert Pirsig's "quality." I try to genuinely savor the entirety of the food and the places I photograph. In that way, something copiously un-special can come to seem like an exotic time capsule. If you can learn to find joy in that kind of unselfconscious, unpretentious thing, you'll be a lot happier in life.

What has food taught you about love?

In every place I've lived since leaving home, my grandmother has always regularly mailed me batches of her homemade flour tortillas every few months. For a New Mexican with deep roots, a homemade tortilla is pure love, and the ones your grandma makes are that love's ultimate expression. As children, we all stole bits of salty, gummy, floury raw masa from the well-worn mixing bowl before they were rolled out, and we waited excitedly as the tortilla came off the hot comal one by one. We all know it's an act of kindness to cook for someone, but it's a true blue act of love to send someone far away a tiny, genuine piece of home.

My best friend, when I was in graduate school in London, was from Bombay. She made the most exquisite okra I've ever tasted. She and I loved to go out for tapas—jamon and sherry—and Australian-style coffee to talk about grandiose things and escape our dingy little flats. To this day, anytime I think of London, as much as I think of watercress sandwiches, greasy, vinegary chip shops, Sunday roasts and good ale, I think of jamon and sherry, flat whites and, especially, that okra. Those things together came to embody love and home for a time in my life that I remember very fondly.

How do you feel about eating alone?

Oh my god, I adore eating alone. It's honestly one of my favorite parts of roadtripping solo. I thought about that a lot while in Italy, where it is exceedingly rare to eat alone, but I braved it a few times anyway. Whenever I roll into a new city, my first move is to look up all the local old-school haunts—Italian red sauce joints, smoky wood-and-naugahyde-lined steakhouses, classic hotel restaurants with ornate fixtures and thick carpets—and always pick the one that looks most likely to lead to a good conversation and maybe a good photo or two. I love places where real life mobsters hang out, like Mancini's Char House in Saint Paul; American classics in decidedly non-foodie cities, like the St. Elmo steakhouse in Indianapolis with its insanely horseradish-rich shrimp cocktails; or glorious old repositories of family and local history, like the Pekin Noodle Parlor in Butte, which just so happens to be the oldest currently-operating Chinese restaurant in America. Breakfast alone at the countertop-only Fountain Room at the Beverly Hills Hotel is my single favorite Los Angeles indulgence.

I was doing some political coverage in Nevada in the lead up to the 2024 election and found a gem of an old place called the Copenhagen Bar in Reno that has absolutely nothing Danish about it, generally doesn't serve food, but does offer a ridiculous, butter-drenched shrimp scampi served on overcooked pasta on just one night a week. And it is really, really good. It's the kind of place where you can still smoke inside, old pros shoot pool in a darkened room stuffed with taxidermy, and flirting with the veteran barmaids will get you a free (and very stiff) drink or two. You can be whoever you want in places like that, and it's so liberating and human.

The world is ending tomorrow! Tell us about your last dinner—the food, your dining companions, the setting, the conversations?

My single favorite dish is gazpacho. I could eat it every single day. I have a rolodex of different gazpacho recipes, each with its own flourishes, and one of my highlights of any given year are those fleeting, magical few weeks when tomatoes at the farmer's market are just perfect. The only problem is, I did a food allergy test a few years ago and, in a cruel twist of fate, the foods my body apparently tolerates least well are tomatoes and garlic. Can you believe that? I had a French friend once who claimed to be allergic to cheese and I razzed him mercilessly for it. It's probably karmic punishment that I'm a Spaniard who's probably allergic to the single most divine varietals of allium and nightshade.

So, like a smoker who knows the perils but indulges anyway, I have not and will not heed the test's advice. If the world were ending tomorrow, I'd just want a vat of the tomato-iest most garlicky gazpacho ever made, drizzled with some rare Italian EVOO, with a side of good crusty French bread, an expertly-cooked steak, and a few glasses of ice-cold Manzanilla sherry. As much as I'd probably enjoy reminiscing with old friends, I'd probably most prefer to just be a fly on the wall at a candlelit table with simple glassware and creaky wooden chairs listening to expansive, spiritual people—a priest, a rabbi, some philosophers, a shaman, a doctor, a psychedelics guide. I’d soak it in, with my gazpacho and sherry, and listen to some good stories about what's awaiting us, what "the end of the world" means, and why we we’re all here in the first place.

Find more of Tag and his photography on his Instagram or website. Or check out his recently launched Substack called Motor—Court.

Who should I interview next? Send me an email at ginarae@substack.com

Lots of love,

Gina Rae

Thanks for reading Feed Me Figs!

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.